Azerbaijani people

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| approx. 22-30 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Predominantly Shiite Muslims; minorities practice Sunni Islam, Christianity, Bahá'í Faith, and Zoroastrianism |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Turkic peoples, Caucasian peoples, Iranian peoples |

The Azerbaijanis[26][27][28][29] are an ethnic group mainly living in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Commonly referred to as Azeris/Āzarīs (آذری - Azərilər) or Azerbaijani Turks[30][31] (Azerbaijani: Azərbaycan türkləri), they also live in a wider area from the Caucasus to the Iranian plateau. The Azeris are predominantly Shia Muslim[32] and have a mixed heritage of Turkic, Caucasian and Iranic elements.

Despite living on two sides of an international border since the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828), after which Iran lost its then northern territories to Russia, the Azeris form a single ethnic group.[33] However, northerners and southerners differ due to nearly two centuries of separate social evolution in Russian/Soviet-influenced Azerbaijan and Iranian Azarbaijan. The Azerbaijani language unifies Azeris, and is mutually intelligible with Turkmen, Qashqai and Turkish (including the dialects spoken by the Iraqi Turkmen), all of which belong to Oghuz, or Western, group of Turkic languages.[34]

Following the Russian-Persian Wars of the 18th and 19th centuries, Persian territories in the Caucasus were ceded to the Russian Empire and[35] the treaties of Gulistan in 1813 and Turkmenchay in 1828 finalized the borders with Russia and Iran.[36][37] The formation of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918 established the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Contents |

History

Part of a series on |

|

|---|---|

| Culture | |

|

Architecture · Art · Cinema · Cuisine |

|

| By country or region | |

|

Iran · Georgia · Russia |

|

| Religion | |

|

Islam · Christianity · Judaism |

|

| Language | |

| Persecution | |

|

March Days · Black January |

|

| Azerbaijan Portal |

|

Azerbaijan is believed to be named after Atropates, a Persian[38][39][40][41][42] satrap (governor) who ruled in Atropatene (modern Iranian Azarbaijan).[43][44] Atropates is derived from Old Persian roots meaning "protected by fire".[45] The current name Azerbaijan is the combination of two Persian words, "Āzar" meaning "(holy) fire" and "pāygān" meaning "the place of". The "G" and "P" were replaced to "J" and "B" respectively during the Arab invasion of Persia, as these two sounds do not exist in Arabic. Azerbaijan has seen a host of inhabitants and invaders, including Medes, Scythians, Persians, Armenians, Greeks, Romans, Khazars, Arabs, Oghuz Turks, Seljuq Turks, Mongols, and Russians.

Ancient Azaris spoke the Ancient Azari language, which belonged to the Iranian branch of Indo-European languages.[46] In the 11th century A.D. with Seljukid conquests, Oghuz Turkic tribes started moving across the Iranian plateau into the Caucasus and Anatolia. The influx of the Oghuz and other Turkmen tribes was further accentuated by the Mongol invasion.[47] Here, the Oghuz tribes divided into various smaller groups, some of whom – mostly Sunni – moved to Anatolia (i.e., the Ottomans) and became settled, while others remained in the Caucasus region and later – due to the influence of the Safawiyya – eventually converted to the Shi'ite branch of Islam. The latter were to keep the name "Turkmen" or "Turcoman" for a long time: from 13th century onwards they gradually Turkified the Iranian-speaking populations of Azerbaijan, thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Oghuz Turkic. However, it is notable that the Turkification of Azaris was completed only by the late 1800s, while the old Iranic speakers can still be found in tiny isolated recesses of the mountains or other remote areas (such as Harzand, Galin Guya, Shahrud villages in Khalkhal and Anarjan). Today, this Turkic-speaking population is also known as Azeris.[48]

Ancient period

Caucasian Albanians are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of the region where modern day Republic of Azerbaijan is located.[43] Early Iranian settlements included the Scythians in the ninth century BC.[49] Following the Scythians, the Medes came to dominate the area to the south of the Aras.[43] The Medes forged a vast empire between 900-700 BC, which was integrated into the Achaemenids Empire around 550 BC. During this period, Zoroastrianism spread in the Caucasus and Atropatene. The Achaemenids in turn were defeated by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, but the Median satrap Atropates was allowed to remain in power. Following the decline of the Seleucids in Persia in 247 BC, an Armenian Kingdom exercised control over parts of Caucasian Albania between 190 BC to 387 AD.[50][51] Caucasian Albanians established a kingdom in the first century BC and largely remained independent until the Persian Sassanids made the kingdom a vassal state in 252 AD.[43]:38 Caucasian Albania's ruler, King Urnayr, officially adopted Christianity as the state religion in the fourth century AD, and Albania would remain a Christian state until the 8th century.[52][53] Sassanid control ended with their defeat by Muslim Arabs in 642 AD.[29]

Medieval period

Muslim Arabs defeated the Sassanids and Byzantines as they marched into the Caucasus region. The Arabs made Caucasian Albania a vassal state after the Christian resistance, led by Prince Javanshir, surrendered in 667.[43]:71 Between the ninth and tenth centuries, Arab authors began to refer to the region between the Kura and Aras rivers as Arran.[43]:20 During this time, Arabs from Basra and Kufa came to Azerbaijan and seized lands that indigenous peoples had abandoned; the Arabs became a land-owning elite.[54] Conversion to Islam was slow as local resistance persisted for centuries and resentment grew as small groups of Arabs began migrating to cities such as Tabriz and Maraghah. This influx sparked a major rebellion in Iranian Azarbaijan from 816–837, led by a local Zoroastrian commoner named Bābak.[55] However, despite pockets of continued resistance, the majority of the inhabitants of Azerbaijan converted to Islam. Later on, in the 10th and 11th centuries, Kurdish dynasties of Shaddadid and Rawadid ruled parts of Azerbaijan.

In the middle of the eleventh century, the Seljuq dynasty overthrew Arab rule and established an empire that encompassed most of Southwest Asia. The Seljuk period marked the influx of Oghuz nomads into the region and, thus, the beginning of the turkification of Azerbaijan as the West Oghuz Turkic language supplanted earlier Caucasian and Iranian ones.[49][56]

However, Iranian cultural influence survived extensively, as evidenced by the works of then contemporary writers such as Persian poet Nezāmī Ganjavī. The emerging Turkic identity was chronicled in epic poems or dastans, the oldest being the Book of Dede Korkut, which relate allegorical tales about the early Turks in the Caucasus and Asia Minor.[43]:45 Turkic dominion was interrupted by the Mongols in 1227 and later the Mongols and Tamerlane ruled the region until 1405. Turkic rule returned with the Sunni Qara Qoyunlū (Black Sheep Turkmen) and Aq Qoyunlū (White Sheep Turkmen), who dominated Azerbaijan until the Shi'a Safavids took power in 1501.[43]:113[54]:285

Modern period

The Safavids, who rose from Iranian Azerbaijan and lasted until 1722, established the modern Iranian state.[57][58][59] Noted for achievements in state building, architecture, and the sciences, the Safavid state crumbled due to internal decay and external pressures from the Russians and Afghans. The Safavids encouraged and spread Shi'a Islam which is an important part of the national identity of Iranian Azerbaijani people as well as many Azerbaijanis north of the Aras. The Safavids encouraged the arts and culture and Shah Abbas the Great created an intellectual atmosphere which according to some scholars was a new Golden Age of Persia.[60] He reformed the government and the military, and responded to the needs of the common people.[60]

The brief Ottoman occupation followed the Safavid state. After the defeat of Afghans and the re-conquest by Nadir Shah Afshar, a chieftain from Khorasan, tried to stabilize the internal affair by balancing the power of the Shi'a.[54]:300 The brief reign of Karim Khan came next, followed by the Qajars, who ruled Azarbaijan and Iran starting in 1779.[43]:106 Russia loomed as a threat to Persian holdings in the Caucasus in this period. The Russo-Persian Wars began in the eighteenth century and ended in the early nineteenth century with the Gulistan Treaty of 1813 and the Turkmenchay Treaty in 1828, which officially gave the Caucasian portion of Qajar Iran to the Russian Empire.[45]

Iranian Azerbaijan's role in the Iranian constitutional revolution cannot be underestimated. The greatest figures of the democracy seeking revolution Sattar Khan[61] and Bagher Khan were both from Iranian Azerbaijan. The Constitutional Revolution of 1906–11 shook the Qajar dynasty, whose kings had virtually sold the country to the tobacco and oil interests of the British Empire and had lost territory to the Russian empire. A parliament (Majlis) came into existence by the efforts of the constitutionalists. It was accompanied in some regions by a peasant revolt against tax collectors and landlords, the only indigenous mainstay of the monarchy. Pro-democracy newspapers appeared, and Iranian intellectuals began to relish the modernist breezes blowing from Paris and Petrograd. The Qajar Shah and his British advisers crushed the Constitutional Revolution, but the demise of the dynasty could not be long postponed. The last Shah of the Qajar dynasty was soon removed by a military coup led by Reza Khan, an officer of an old Cossack regiment, which had been created by Czarist Russia and officered by Russians to protect the Qajar ruler and Russian interests. In the quest of imposing national homogeneity on the country where half of the population consisted of ethnic minorities, Reza Shah issued in quick succession bans on the use of Azerbaijani language on the premises of schools, in theatrical performances, religious ceremonies, and, finally, in the publication of books.[62]

With the dethronement of Reza Shah in September 1941, Russian troops captured Tabriz and northwestern Persia for military and strategic reasons. Azerbaijan People's Government, a client state set up by the order of Stalin himself, under leadership of Sayyid Jafar Pishevari was proclaimed in Tabriz[63] However, under pressure by the Western countries, the Soviet army was soon withdrawn, and the Iranian government regained control over Iranian Azerbaijan by the end of 1946.

According to Professor. Gary R. Hess:

| “ | On December 11, an Iranian force entered Tabriz and the Peeshavari government quickly collapsed. Indeed the Iranians were enthusiastically welcomed by the people of Azerbaijan, who strongly preferred domination by Tehran rather than Moscow. The Soviet willingness to forego its influence in (Iranian) Azerbaijan probably resulted from several factors, including the realization that the sentiment for autonomy had been exaggerated and that oil concessions remained the more desirable long-term Soviet Objective.[64] | ” |

While the Azeris in Iran largely integrated into modern Iranian society, the Azeris in what is today called the Republic of Azerbaijan lived through the transition from the Russian Empire to brief independence from 1918–1920 and then incorporation into the Soviet Union despite pleas by Woodrow Wilson for their independence at the Treaty of Versailles conference. The Republic of Azerbaijan achieved independence in 1991, but became embroiled in a war over the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.

Origins

In many references, Azerbaijanis are designated as a Turkic people, due to their Turkic language.[65][66][67] However, modern-day Azerbaijanis are believed to be primarily the descendants of the Caucasian Albanian[68][69] and Iranic peoples who lived in the areas of the Caucasus and northern Iran, respectively, prior to Turkification. Various historians including Vladimir Minorsky explain how largely Iranian and Caucasian populations became Turkish-speaking:

| “ | In the beginning of the 5th/11th century the Ghuzz hordes, first in smaller parties, and then in considerable numbers, under the Seljuqids occupied Azarbaijan. In consequence, the Iranian population of Azarbaijan and the adjacent parts of Transcaucasia became Turkophone while the characteristic features of Ādharbāyjānī Turkish, such as Persian intonations and disregard of the vocalic harmony, reflect the non-Turkish origin of the Turkicised population.[70] | ” |

Thus, centuries of Turkic migration and turkification of the region helped to formulate the contemporary Azerbaijani ethnic identity.

Turkification

"Turkic penetration probably began in the Hunnic era and its aftermath", there is big evidence to indicate "permanent settlements".[66] The earliest major Turkic incursion began and accelerated during the Seljuk period.[66] The migration of Oghuz Turks from present-day Turkmenistan, which is attested by linguistic similarity, remained high through the Mongol period, as many troops under the Ilkhans were Turkic. By the Safavid period, the Turkification of Azerbaijan continued with the influence of the Kizilbash. The very name Azerbaijan is derived from the pre-Turkic name of the province, Azarbayjan or Adarbayjan, and illustrates a gradual language shift that took place as local place names survived Turkification, albeit in altered form.[71]

Few academics view the Turkic linguistic assimilation of predominantly non-Turkic-speaking indigenous peoples and smaller groups of Turkic tribes as the most likely source of Azerbaijani national background.[43][45]

Iranian origin

The Iranian origins of the Azeris likely derive from ancient Iranic tribes, such as the Medes in Iranian Azarbaijan, and Scythian invaders who arrived during the eighth century BCE. It is believed that the Medes mixed with Mannai.[72] Ancient written accounts, such as one written by Arab historian Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Masudi (896-956), attest to an Iranian presence in the region:

| “ | The Persians are a people whose borders are the Mahat Mountains and Azarbaijan up to Armenia and Aran, and Bayleqan and Darband, and Ray and Tabaristan and Masqat and Shabaran and Jorjan and Abarshahr, and that is Nishabur, and Herat and Marv and other places in land of Khorasan, and Sejistan and Kerman and Fars and Ahvaz...All these lands were once one kingdom with one sovereign and one language...although the language differed slightly. The language, however, is one, in that its letters are written the same way and used the same way in composition. There are, then, different languages such as Pahlavi, Dari, Azari, as well as other Persian languages.[73] | ” |

Scholars see cultural similarities between modern Persians and Azeris as evidence of an ancient Iranian influence.[74] Archaeological evidence indicates that the Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism was prominent throughout the Caucasus before Christianity and Islam and that the influence of various Persian Empires added to the Iranian character of the area.[75] It has also been hypothesized that the population of Iranian Azarbaijan was predominantly Persian-speaking before the Oghuz arrived. This claim is supported by the many figures of Persian literature, such as Qatran Tabrizi, Shams Tabrizi, Nezami, and Khaghani, who wrote in Persian prior to and during the Oghuz migration, as well as by Strabo, Al-Istakhri, and Al-Masudi, who all describe the language of the region as Persian. The claim is mentioned by other medieval historians, such as Al-Muqaddasi.[71][76] Other common Perso-Azeribaijani features include Iranian place names such as Tabriz[77] and the name Azerbaijan itself.

Encyclopaedia Iranica explains that "The Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan (q.v.) are mainly descended from the earlier Iranian speakers, several pockets of whom still exist in the region."[78] The modern presence of the Iranian Talysh and Tats in Azerbaijan is further evidence of the Iranian ethnic influence in the region.[79][80] As a precursor to these modern groups, the ancient Azaris are also hypothesized as ancestors of the modern Azerbaijanis.

Caucasian origin

According to Encyclopædia Britannica about Azeris in the Republic of Azerbaijan:

| “ | The Azerbaijani are of mixed ethnic origin, the oldest element deriving from the indigenous population of eastern Transcaucasia and possibly from the Medians of northern Persia.[81] | ” |

The Caucasian origin mostly applies to the Azeris of the Caucasus, most of whom are now inhabitants of the Republic of Azerbaijan. There is evidence that, despite repeated invasions and migrations, aboriginal Caucasians may have been culturally assimilated, first by Iranians and later by the Oghuz. Considerable information has been learned about the Caucasian Albanians including their language, history, early conversion to Christianity, and close ties to the Armenians. Many academics believe that the Udi language, still spoken in Azerbaijan, is a remnant of the Albanians' language.[53][82]

This Caucasian influence extended further south into Iranian Azarbaijan. During the 1st millennium BCE, another Caucasian people, the Mannaeans (Mannai) populated much of Iranian Azarbaijan. Weakened by conflicts with the Assyrians, the Mannaeans are believed to have been conquered and assimilated by the Medes by 590 BCE.[83]

Genetics

Some new genetic studies suggest that recent erosion of human population structure might not be as important as previously thought, and overall genetic structure of human populations may not change with the immigration events but in the Azerbaijani case; some Azeris of Azerbaijan republic genetically resemble other Caucasian people like Armenians[84] and people in the Azarbaijan region of Iran to other Iranians.[85]

According to a study of Eurasia's population by the American Society of Human Genetics, the different Iranian populations show a striking degree of homogeneity and nonsignificant FST values among themselves.[86] It seems that the people are largely Iranian settlers both before and after Islam.

Studies conducted at Cambridge University

A recent study of the genetic landscape of Iran was completed by a team of Cambridge geneticists led by Dr. Maziar Ashrafian Bonab (an Iranian Azarbaijani).[87] Bonab remarked that his group had done extensive DNA testing on different language groups, including Indo-European and non Indo-European speakers, in Iran.[88] The study found that the Azerbaijanis of Iran do not have a similar FSt and other genetic markers found in Anatolian and European Turks. However, the genetic Fst and other genetic traits like MRca and mtDNA of Iranian Azeris were identical to Persians in Iran.

Studies conducted in the Caucasus

A 2003 study found that: "Y-chromosome haplogroups indicate that Indo-European-speaking Armenians and Turkic-speaking Azerbaijanians (of the Republic of Azerbaijan) are genetically more closely related to their geographic neighbors in the Caucasus than to their linguistic neighbors elsewhere."[89] The authors of this study suggest that this indicates a language replacement of indigenous Caucasian peoples. There is evidence of genetic admixture derived from Central Asians (specifically Haplogroup H12), notably the Turkmen, that is much higher than that of their neighbors, the Georgians and Armenians.[90] MtDNA analysis indicates that the main relationship with Iranians is through a larger West Eurasian group that is secondary to that of the Caucasus, according to a study that did not include Azeris, but Georgians who have clustered with Azeris in other studies.[91] The conclusion from the testing shows that the Caucasian Azeris are a mixed population with relationships, in order of greatest similarity, with the Caucasus, Iranians and Near Easterners, Europeans, and Turkmen. Other genetic analysis of mtDNA and Y-chromosomes indicates that Caucasian populations are genetically intermediate between Europeans and Near Easterners, but that they are more closely related to Near Easterners overall.[89] Another study, conducted in 2003 by the Russian Journal of Genetics, links Iranians in Azerbaijan (the Talysh and Tats) with Turkic Azerbaijanis of the Republic:

| “ | the genetic structure of the populations examined with the other Iranian-speaking populations (Persians and Kurds from Iran, Ossetins, and Tajiks) and Azerbaijanis showed that Iranian-speaking populations from Azerbaijan were closer to Azerbaijanis and Iranis than to Iranian-speaking populations inhabiting other world regions.[92] | ” |

Ethnonym

Historically the Turkic speakers[93] of Iranian Azerbaijan and the Caucasus called themselves or were referred to by others as Muslims, Turks, or Ajams (by Kurds),[94] and religious identification prevailed over ethnic identification. When the South Caucasus became part of the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century, the Russian authorities, who traditionally referred to all Turkic people as Tatars, defined Tatars living in the Transcaucasus region as Caucasian or Aderbeijanskie (Адербейджанские) Tatars to distinguish them from other Turkic geoups.[95] The Russian Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, written in the 1890s, also refers to Tatars in Azerbaijan as Aderbeijans (адербейджаны).[96] According to the article Turko-Tatars of the above encyclopedia:

| “ | some scholars (Yadrintsev, Kharuzin, Chantre) proposed to change the terminology of some Turko-Tatar people who have little in common with the Turks, for instance, to call Aderbaijani Tatars (Iranians by race) Aderbaijans (адербайджаны), but this has not yet taken root...[97] | ” |

This ethnonym was also used by Joseph Deniker:

| “ | [The purely linguistic] grouping [does not] coincide with the somatological grouping: thus the Aderbeijani of the Caucasus and Persia, who speak a Turkish language, have the same physical type as the Hadjemi-Persians, who speak an Iranian tongue.[98] | ” |

In Azerbaijani-language publications, the expression "Azerbaijani nation" referring to those who were known as Tatars of the Caucasus first appeared in the newspaper Kashkul in 1880.[99]

Demographics and society

There are an estimated 24 to 33 million Azerbaijanis in the world, but census figures are difficult to verify. The vast majority live in Azerbaijan and Iranian Azarbaijan. Between 16 and 23 million Azeris live in Iran, mainly in the northwestern provinces. Approximately 7.6 million Azeris are found in the Republic of Azerbaijan. A diaspora, possibly numbering in the millions, is found in neighboring countries and around the world. There are sizable communities in Turkey, Georgia, Russia, UK, USA, Canada, Germany and other countries.[100]

While population estimates in Azerbaijan are considered reliable due to regular censuses taken, the figures for Iran remain questionable. Since the early twentieth century, successive Iranian governments have avoided publishing statistics on ethnic groups.[101] Unofficial population estimates of Azeris in Iran range from 20–24%.[4][102] However, many Iran scholars, such as Nikki Keddie, Patricia J. Higgins, Shahrough Akhavi, Ali Reza Sheikholeslami, and others, claim that Azeris may comprise as much as one third of Iran's population.[101][103][104]

A large expatriate community of Azerbaijanis is found outside Azerbaijan and Iran. According to Ethnologue, there were over 1 million Azerbaijani-speakers of the north dialect in southern Dagestan, Armenia, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan as of 1993.[100] Other sources, such as national censuses, confirm the presence of Azeris throughout the former Soviet Union. The Ethnologue figures are outdated in the case of Armenia, where the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has affected the population of Azeris.[105] Ethnologue further reports that an additional 1 million South Azeris live outside Iran, but these figures most likely are a reference to the Iraqi Turkmen, a distinct though related Turkic people.[106]

Azeris in Azerbaijan

By far the largest ethnic group in Azerbaijan (over 90%), the Azeris generally tend to dominate most aspects of the country. Unlike most of their ethnic brethren in Iran, the majority of Azeris are secularized from decades of official Soviet atheism. The literacy rate is very high, another Soviet legacy, and is estimated at 99.5%.[107] Whereas most urban Azeris are educated, education remains comparatively lower in rural areas. A similar disparity exists with healthcare.

Azeri society has been deeply impacted by the war with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, which has displaced nearly 1 million Azeris and put strains upon the economy.[108] Azerbaijan has benefited from the oil industry, but high levels of corruption have prevented greater prosperity for the masses.[109] Many Azeris have grown frustrated over the political process in Azerbaijan as the election of current president Ilham Aliyev has been described as "marred by allegations of corruption and brutal crackdowns on his political opposition".[110][111] Despite these problems, there is a renaissance in Azerbaijan as positive economic predictions and an active political opposition appear determined to improve the lives of average Azeris.[49][112]

Azeris in Iran

Azerbaijanis in Iran are mainly found in the northwest provinces: East Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, parts of Hamedan, Qazvin, West Azerbaijan and Markazi.[113] Many others live in Tehran, Fars Province, and other regions.[29] Generally, Azeris in Iran were regarded as "a well integrated linguistic minority" by academics prior to Iran's Islamic Revolution.[114][115] Despite friction, Azerbaijanis in Iran came to be well represented at all levels of "political, military, and intellectual hierarchies, as well as the religious hierarchy".[101]

Resentment came with Pahlavi policies that suppressed the use of the Azerbaijani language in local government, schools, and the press.[116] However with the advent of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, emphasis shifted away from nationalism as the new government highlighted religion as the main unifying factor. Within the Islamic Revolutionary government there emerged an Azeri nationalist faction led by Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari, who advocated greater regional autonomy and wanted the constitution to be revised to include secularists and opposition parties; this was denied.[117] In May 2006 Iranian Azerbaijan witnessed riots over publication of a cartoon[118] that many Azeris found offensive.[119][120] The cartoon was drawn by Mana Neyestani, an ethnic Azeri, who was fired along with his editor as a result of the controversy.[121][122]

Despite sporadic problems, Azeris are an intrinsic community within Iran. Currently, the living conditions of Azeris in Iran closely resemble that of Persians:

| “ | The life styles of urban Azerbaijanis do not differ from those of Persians, and there is considerable intermarriage among the upper classes in cities of mixed populations. Similarly, customs among Azerbaijani villagers do not appear to differ markedly from those of Persian villagers.[29] | ” |

Andrew Burke writes:

| “ | Azeris are famously active in commerce and in bazaars all over Iran their voluble voices can be heard. Older Azeri men wear the traditional wool hat, and their music & dances have become part of the mainstream culture. Azeris are well integrated, and many Azeri-Iranians are prominent in Persian literature, politics, and clerical world.[123] | ” |

Azeris in Iran are in high positions of authority with the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei currently sitting as the Supreme Leader.

Relations between both sides

In contrast to what one may at first presume, Azeris on both sides are politically conservative towards one another despite the cultural and linguistic gel. The main, and possibly only source of interaction and unification between the two lies in the city of Astara. Astara is a multi-bordered city with the north under the occupation of Azerbaijan and south under Iran and this enables residents of both sides to communicate and trade easily.[124] Iranians often cross into the Azeri section to purchase alcohol freely and Azeris go into Iran to gain resources that are of a cheaper amounts.[124]

Culture

In many respects, Azeris are Eurasian and bi-cultural, as northern Azeris have absorbed Russo-Soviet and Eastern European influences, whereas the Azeris of the south have remained within the Turko-Iranian and Persianate tradition. Modern Azeri culture includes significant achievements in literature, art, music, and film.

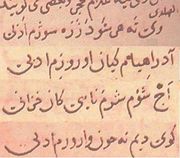

Language and literature

The Azerbaijanis speak Azerbaijani (sometimes called Azerbaijani Turkish or Azeri), one of branches of Oghuz Turkic languages. Oghuz Turks entered in Azerbaijan in 11th and 12th century CE and Azeri went through a gradual development before assuming its present form.[125] Early Oghuz was mainly an oral language. The origins of the later compiled epics and heroic stories of Dede Korkut, is probably this period. Oral tradition continues for the next two hundred years. The first accepted Oghuz Turkic text goes back to 15th century. The beginning of written, classical Azeri literature was after the Mongol invasion.[125] Some of the earliest Azeri writings of the past are traced back to the poet Nasimi (died 1417) and then decades later Fuzûlî (1483–1556). Ismail I, Shah of Safavid Persia wrote Azeri poetry under the pen name Khatâ'i. Modern Azeri literature continued with a traditional emphasis upon humanism, as conveyed in the writings of Samad Vurgun, Shahriar, and many others.[126]

Azeris are generally bilingual, often fluent in either Russian (in Azerbaijan) or Persian (in Iran). As of 1996, around 38% of Azerbaijan's roughly 8,000,000 population spoke Russian fluently.[127] Moreover, in 1999, around 2,700 Azeris in the Azerbaijan Republic (0.04% of the total Azeri population) reported Russian as their mothertongue.[128] An Iranian survey (2002) revealed that 90.0% of the sample household population in Iran is able to speak Persian, 4.6% can only understand it, and 5.4% can neither speak nor understand Persian. Azeri is the most spoken minority language in an Iranian household (24%).[129]

Religion

The majority of Azerbaijanis are Twelver Shi'a Muslims. Religious minorities include Sunni Muslims (mainly Hanafi),[130] Zoroastrians, Christians and Bahá'ís. Azeris in the Republic of Azerbaijan have an unknown number showing no religious affiliation, since being in a secular country. Many describe themselves as cultural Muslims.[49][131] There is a small number of Naqshbandi Sufis among Muslim Azeris.[132] Christian Azeris number around 5,000 people in the Republic of Azerbaijan and consist mostly of recent converts.[133] Some Azeris from rural regions retain pre-Islamic animist beliefs, such as the sanctity of certain sites and the veneration of certain trees and rocks.[134] In the Republic of Azerbaijan traditions from other religions are often celebrated in addition to Islamic holidays, including Norouz and Christmas. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijanis have increasingly returned to their Islamic heritage as recent reports indicate that many Azerbaijani youth are being drawn to Islam.[135] A recent study indicated that radical Islam is growing in the nation, capturing the attention of some ultra-secularists.[136]

Performance art

Azeris express themselves in a variety of artistic ways including dance, music, and the media. Azeri folk dances are ancient and similar to that of their neighbours in the Caucasus and Iran. The group dance is a common form found from southeastern Europe to the Caspian Sea. In the group dance the performers come together in a semi-circular or circular formation as, "The leader of these dances often executes special figures as well as signaling and changes in the foot patterns, movements, or direction in which the group is moving, often by gesturing with his or her hand, in which a kerchief is held."[137] Solitary dances are performed by both men and women and involve subtle hand motions in addition to sequenced steps.

Azeri musical tradition can be traced back to singing bards called Ashiqs, a vocation that survives to this day. Modern Ashiqs play the saz (lute) and sing dastans (historical ballads).[138] Other musical instruments include the tar (another type of lute), duduk or balaban (a wind instrument), kamancha (fiddle), and the dhol (drums). Azeri classical music, called mugham, is often an emotional singing performance. Composers Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Gara Garayev and Fikret Amirov created a hybrid style that combines Western classical music with mugham. Other Azeris, notably Vagif Mustafa Zadeh and Aziza Mustafa Zadeh, mixed jazz with mugham. Some Azeri musicians have received international acclaim, including Rashid Behbudov (who could sing in over eight languages) and Muslim Magomayev (a pop star from the Soviet era).

Meanwhile in Iran, Azeri music has taken a different course. According to Iranian Azeri singer Hossein Alizadeh, "Historically in Iran, music faced strong opposition from the religious establishment, forcing it to go underground."[139] As a result, most Iranian Azeri music is performed outside of Iran amongst exile communities.

Azeri film and television is largely broadcast in Azerbaijan with limited outlets in Iran. Some Azeris have been prolific film-makers, such as Rustam Ibragimbekov, who wrote Burnt by the Sun, winner of the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1994. Many Iranian Azeris have been prominent in the cinematic tradition of Iran, which has received critical praise since the 1980s.

Sports

Sports have historically been an important part of Azeri life. Numerous competitions were conducted on horseback and praised by poets and writers such as Qatran Tabrizi and Nezami Ganjavi.[140] Other ancient sports include wrestling, javelin throwing and ox-wrestling.

The Soviet legacy has in modern times propelled some Azeris to become accomplished athletes at the Olympic level.[140] The Azeri government supports the country's athletic legacy and encourages Azeri youth to take part. Football is very popular in both Azerbaijan and Iranian Azarbaijan. There are many prominent Azeri soccer players such as Ali Daei, the world's all-time leading goal scorer in international matches and the former captain of the Iran national soccer team. Azeri athletes have particularly excelled in weight lifting, gymnastics, shooting, javelin throwing, karate, boxing, and wrestling.[141] Weight lifters, such as Iran's Hossein Reza Zadeh, world's super heavyweight lifting record holder and two times Olympic champion in 2000 and 2004 and Nizami Pashayev, who won the European heavyweight title in 2006, have excelled at the international level.

Chess is another popular pastime in Azerbaijan. The country has produced many notable players, such as Teimour Radjabov and Shahriyar Mammadyarov, both highly ranked internationally.

Institutions

Azerbaijan and Iranian Azerbaijan have developed distinct institutions as a result of divergent socio-political evolution. Azerbaijan began the twentieth century with institutions based upon those of Russia and the Soviet Union, with strict state control over most aspects of society. Since, they have moved towards the adoption of Western social models as of the late twentieth century. Since independence, relaxed state controls have allowed local civil society to develop. In contrast, in Iranian Azerbaijan Islamic theocratic institutions dominate nearly all aspects of society, with most political power in the hands of the Supreme Leader of Iran and the Council of Guardians. Yet both societies are in a state of change. In Azerbaijan there is a secular democratic system that is mired in political corruption and charges of election fraud. Azerbaijan's civil society is a work in progress:

| “ | The lack of more 'modern' forms of self-organization and the experience of liberal democratic rule is the main reason why the building of civil society and the process of democratization in Azerbaijan takes place in a parallel rather than linear way. In the result, today Azerbaijan society may be characterized mostly as quasi civil and quasi democratic society the structures and institutions of which having signs of civil and democratic society from the standpoint of their level of development do not correspond to the modern criteria of the modern democratic society.[142] | ” |

Despite these problems Azerbaijan has an active political opposition that seeks more expansive democratic reforms.[112] Azeris in Iran remain intertwined with the Islamic republic's theocratic regime and lack any significant civil society of a secular nature that can pose a major challenge. There are signs of civil unrest due to the policies of the Iranian government in Iranian Azarbaijan and increased interaction with fellow Azeris in Azerbaijan and satellite broadcasts from Turkey have revived Azeri nationalism.[143]

Women

Azeri females have historically struggled against a legacy of male domination but have made great strides since the twentieth century. In Azerbaijan, women were granted the right to vote in 1919.[144] Women have attained Western-style equality in major cities such as Baku, although in rural areas more traditional views remain.[49][145] Some problems that are especially prevalent include violence against women, especially in rural areas. Crimes such as rape are severely punished in Azerbaijan, but rarely reported, not unlike other parts of the former Soviet Union.[146] Azeri women were forced to "give up the veil".[147] Women are underrepresented in elective office but have attained high positions in parliament. An Azeri woman is the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in Azerbaijan, and two others are Justices of the Constitutional Court. As of 6 November 2005, women constituted 12% of all MPs (fifteen seats in total) in the National Assembly of Azerbaijan.[148] The Republic of Azerbaijan is also one of the few Muslim countries where abortion is available on demand.[149] The human rights ombudsman, Elmira Suleymanova, is a woman.

In Iran, the continued unequal treatment of women has been met with increasingly vocal protests, including that of Shirin Ebadi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2003 for her strong advocacy for women's rights. A groundswell of grassroots movements have emerged seeking gender equality since the 1980s.[29][150] Regular protests take place in defiance of government bans and are often dispersed through violence, as in June 2006 when "[t]housands of women and male supporters came together on June 12 in Haft Tir Square in Tehran" and were dispersed through "brutal suppression".[151] Past Iranian leaders, such as Mohammad Khatami, promised women greater rights, but the government has opposed changes that they interpret as contrary to Islamic doctrine. As of 2004, nine Azeri women have been elected to parliament (Majlis) and while most are committed to social change, some represent conservative positions regarding gender issues.[152] The social fate of Azeri women largely mirrors that of other women in Iran.

See also

- History of the name Azerbaijan

- List of Azeris

- Origin of the Azeris

Notes and references

- ↑ "Azerbaijanis ethnic people in all Countries"

- ↑ Library of Congress, Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. ""Ethnic Groups and Languages of Iran"". http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Iran.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-02} 16% estimated in 2009.

- ↑ "Peoples of Iran" in Looklex Encyclopedia of the Orient. Retrieved on 22 January 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Iran: People", CIA: The World Factbook: 24% of Iran's total population. Retrieved on 22 January 2009.

- ↑ G. Riaux, "The Formative Years of Azerbaijani Nationalism in Post-Revolutionary Iran", Central Asian Survey, 27(1): 45-58, March 2008: 25% of Iran's total population (p. 46). Retrieved on 22 January 2009.

- ↑ "Borders and Brethren: Iran and the Challenge of Azerbaijani Identity" in The Azerbaijani Population by Brenda Shaffer, pp. 221–225. The MIT Press (2003), ISBN 0-262-19477-5.

- ↑ Swietochowski, Tadeusz; Collins, Brian C. (1999). Historical dictionary of Azerbaijan. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-3550-9. pg 28: "15 million (1999)"

- ↑ "Population by ethnic groups", The State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan Republic . Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan: People", CIA Factbook. Azeri ethnic percentage of 90.6% used to calculate population derived from Azeri census . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ "Turkey: Religions & Peoples", Encyclopedia of the Orient . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ "Azerbaijanis in Russia", 2002 Russian Census . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ State Statistics Department of Georgia: 2002 census . Retrieved 16 July 2006.

- ↑ Ethnic Composition of Kazakhstan (1999 census) . Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ↑ "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001", Ukraine Census 2001 . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ Azerbaijan Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Bilateral relations with the Netherlands: Diaspora. NB Of these, 7,000 are immigrants from Azerbaijan. Retrieved on 3 June 2009

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 http://www.stat.kg/stat.files/din.files/census/5010003.pdf National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyz Republic 2009. Retrieved on 4 September 2010

- ↑ [1]. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- ↑ First, Second, and Total Responses to the Ancestry Question by Detailed Ancestry Code: 2000. This number includes both primary and secondary ancestry. . Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ↑ List of Canadians by ethnicity (following 2006 census). NB Canadian census on ancestry may not reflect current ethnic affiliation in Canada. (retrieved 7 June 2006). In the 2006 census, 1,480 people indicated 'Azeri'/'Azerbaijani' as a single response and 1,985 - as part of multiple origins.

- ↑ Population Register of Latvia (2000). NB Of these, only 232 (13.7%) are Latvian citizens.

- ↑ Azerbaijan Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Azerbaijan-Austria relations: Diaspora Info (February 2008). NB Of these, about 70-75% are Iranian Azeris, 15-20% are Turkish Azeris and 5-10% are Azeris originally from Azerbaijan and the former Soviet Union.

- ↑ [2]Census of Lithuania.

- ↑ Estonia: Population Census of 2000: select "Azerbaijani" under "Ethnic nationality". NB Of these, only 162 held Estonian citizenship as of 31 March 2000.

- ↑ Jeyran Bayramova. Рахман Мустафаев: "Греция - это дружественное соседнее государство, с которым можно и нужно выстраивать взаимовыгодное сотрудничество во всех сферах". Zerkalo. 3 July 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ↑ 2006 Australian Census. NB According to the 2006 census, 290 people living in Australia identified themselves as of Azeri ancestry, although the Australian-Azeri community is estimated to be larger. . Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ↑ Joshua Project. "Ethnic People Groups of the Turkic Peoples Affinity Bloc". Joshua Project. http://www.joshuaproject.net/affinity-blocs.php?rop1=A015. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, North —". Rosettaproject.org. http://www.rosettaproject.org/archive/azj. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ↑ (pronounced /ˌæzərbaɪˈdʒɑːni/; in Azeri: Azərbaycanlılar, Azeris/Azərilər, Azeri Turks/Azərilər; Azeri Cyrillic: Азәриләр, Azeri: آذری لر ) or Azarbaijanis

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 "Iran", US Library of Congress Country Studies (retrieved 7 June 2006). (in Iran; also Azaris, Turks/Torks)

- ↑ Helena Bani-Shoraka. "Language Policy and Language Planning: Some Definitions" in Annika Rabo, Bo Utas. The Role of the State in West Asia, Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, 2005, ISBN 91-86884-13-1, 9789186884130, p. 144

- ↑ Stephan Thernstrom, Ann Orlov, Oscar Handlin. Harvard Encyclopedia of American ethnic groups, Harvard University Press, 1981, p. 171, quote: In their homeland the Azerbaijanis, or Azerbaijani Turks as they are sometimes called...

- ↑ Robertson, Lawrence R. (2002). Russia & Eurasia Facts & Figures Annual. Academic International Press. p. 210. ISBN 0875691994, 9780875691992. http://books.google.com/books?id=ye1oAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani", Encyclopedia Britannica,Russian suzerainty of Azerbaijan . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ Suny, Ronald G.; Nichol, James; Slider, Darrell L. (1996). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. DIANE Publishing. p. 105. ISBN 0788128132, 9780788128134. http://books.google.com/books?id=B2W1YOG3N10C&pg=PA105.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan", MSN Encarta . Retrieved 25 January 2007. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Sidney Harcave, Russia, a history, Edition: 6, Lippincott, 1968, Page 267

- ↑ Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbors in the Middle East...by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field, Universal-Publishers, 2007, ISBN 1-58112-933-5, 9781581129335, Pages 372

- ↑ Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States by James Minahan, published in 2000, page 20

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Atropates (Biography)". Livius.org. http://www.livius.org/as-at/atropates/atropates.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ Chamoux, Francois. Hellenistic Civilization. Blackwell Publishing, published 2003, page 26

- ↑ Bosworth, A.B., and Baynham, E.J. Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Oxford, published 2002, page 92

- ↑ Encyclopedia Iranica, "Azerbaijan: Pre-Islamic History", K. Shippmann

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 43.6 43.7 43.8 43.9 Historical Dictionary of Azerbaijan by Tadeusz Swietochowski and Brian C. Collins. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Maryland (1999), ISBN 0-8108-3550-9 . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ Azerbaijan: ethnicity and the ... - Google Books. Books.google.ca. http://books.google.ca/books?id=MybbePBf9YcC&dq=azeri&printsec=frontcover&source=in&hl=en&ei=NraQSb_-B5C4MuOStakL&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=18&ct=result#PPA7,M1. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity under Russian Rule by Audrey Altstadt. Hoover Institution Press (1992), ISBN 0-8179-9182-4 . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranica.com. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/index.isc?Article=http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v3f3/v3f2a88b.html. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Iranica. C. E. Bosworth. Arran". Iranica.com. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v2f5/v2f5a010.html. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ Roy, Olivier (2007). The new Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 184511552X. http://books.google.com/books?id=-eMcn6Ik1v0C&pg=PA7&sig=njHz1tUfPk-uqSpdUzHIbL99wvg#PPA6,M1.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Azerbaijan, US Library of Congress Country Studies . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ "Armenia-Ancient Period", US Library of Congress Country Studies . Retrieved 23 June 2006.

- ↑ Strabo, "Geography", Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University . Retrieved 24 June 2006.

- ↑ "Albania", Encyclopedia Iranica, p. 807 . Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Voices of the Ancients: Heyerdahl Intrigued by Rare Caucasus Albanian Text" by Dr. Zaza Alexidze, Azerbaijan International, Summer 2002 . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 A History of Islamic Societies by Ira Lapidus, p. 48. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1988), ISBN 0-521-77933-2 . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates by Hugh Kennedy, p. 166. Longman Group, London (1992), ISBN 0-582-40525-4. Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ Turkic Languages: Classification - Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ The Safavid Empire, University of Calgary . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Shi'a: The Safavids, Washington State University . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Safavid Empire 1502–1736, Iran Chamber . Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Kathy Sammis, Focus on World History: The First Global Age and the Age of Revolution, pg 39.

- ↑ "Sattar Khan". Iranchamber.com. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/sattarkhan/sattar_khan.php. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ Tadeusz Swietochowski, Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition (ISBN 0-231-07068-3)

- ↑ "Cold War International History Project 1945–46 Iranian Crisis". Wilsoncenter.org. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/index.cfm?topic_id=1409&fuseaction=va2.browse&sort=Collection&item=1945%2D46%20Iranian%20Crisis. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "Gary. R. Hess Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 89, No. 1 (March 1974)" (PDF). http://www.azargoshnasp.net/recent_history/atoor/theiraniancriris194546.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan: People", Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples by Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz (1992), ISBN 3-447-03274-X . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ "Turkic Peoples", Encyclopedia Americana, volume 27, page 276. Grolier Inc., New York (1998) ISBN 0-7172-0130-9. Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Kobishchanov, Yuri et al. Axum. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1979; p. 89

- ↑ Ronald G. Suny: What Happened in Soviet Armenia? Middle East Report, No. 153, Islam and the State. (Jul. – Aug., 1988), pp. 37–40.

- ↑ Minorsky, V.; Minorsky, V. "(Azarbaijan). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 "The spread of Turkish in Azerbaijan", Encyclopedia Iranica, . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Iranica, "Mannea", by R. Zadok"

- ↑ (Al Mas'udi, Kitab al-Tanbih wa-l-Ishraf, De Goeje, M.J. (ed.), Leiden, Brill, 1894, pp. 77-8)

- ↑ "Azerbaijan", Columbia Encyclopedia . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ "Various Fire-Temples", University of Calgary . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Al-Muqaddasi, Ahsan al-Taqāsīm, p. 259 & 378, "... the Azerbaijani language is not pretty [...] but their Persian is intelligible, and in articulation it is very similar to the Persian of Khorasan ...", tenth century, Persia . Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- ↑ "Tabriz" . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ "Report for Talysh", Ethnologue . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ "Report for Tats", Ethnologue . Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- ↑ Azerbaijani." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 5 Apr. 2007 <http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9011540>.

- ↑ "The Udi Language", University of Munich, Wolfgang Schulze 2001/2 . Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ↑ "Mannai", Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 June 2006.

- ↑ "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus" (PDF). http://www.eva.mpg.de/genetics/pdf/Y-paper.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ "Is urbanisation scrambling the genetic structure of human populations?". Pubmedcentral.nih.gov. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800918. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1808191. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5): 827–845. "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor" [3] accessed May, 2010. See Figure 1. excerpt: " Indeed, the different Iranian populations show a striking degree of homogeneity. This is revealed not only by the nonsignificant FST values and the PC plot (fig. 6) but also by the SAMOVA results,.."

- ↑ "Maziar Ashrafian Bonab", Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ "Cambridge Genetic Study of Iran", ISNA (Iranian Students News Agency), 06-12-2006, news-code: 8503-06068 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus: evidence from the Y-chromosome" — Human Genetics (2003) 112 : 255–261 . Retrieved 09 June 2006.

- ↑ "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia", American Journal of Human Genetics, 71:466-482, 2002 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor", American Journal of Human Genetics, 74:827-845, 2004 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ "Genetic Structure of Iranian-Speaking Populations from Azerbaijan Inferred from the Frequencies of Immunological and Biochemical Gene Markers", Russian Journal of Genetics, Volume 39, Number 11, November 2003, pp. 1334-1342(9) . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Azerbaijani article, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Powder Keg in the Middle East by Geoffrey Kemp, Janice Gross Stein. Rowman & Littlefield, 1995; ISBN 0-8476-8075-4; p. 214

- ↑ (Russian) Demoscope Weekly, alphabetical list of people living in the Russian Empire (1895).

- ↑ (Russian) Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. Turks (Тюрки). St. Petersburg, Russia, 1890-1907

- ↑ (Russian) Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. Turko-Tatars (Тюрко-татары). St. Petersburg, Russia, 1890-1907.

- ↑ Joseph Deniker. Races et peuples de la terre. Paris, 1900; p. 294

- ↑ Firouzeh Mostashari. On the religious frontier: Tsarist Russia and Islam in the Caucasus. I.B.Tauris, 2006. ISBN 1850437718; p. 129.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 "Azerbaijani, North: A language of Azerbaijan", Ethnologue report . Retrieved 24 June 2006.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan edited by Ali Banuazizi and Myron Weiner, Part II: Iran. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, N.Y. (1988), ISBN 0-8156-2448-4 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ "Ethnische Gruppen", Iranian embassy in Germany . Retrieved 17 June 2006.

- ↑ Shahrough Akhavi, Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran: Clergy-State Relations in the Pahlavi Period, State University of New York (1980), ISBN 0-87395-456-4. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Nikki Keddie, Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution, Yale University Press (2003), ISBN 0-300-09856-1. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Peace Talks at Key West between Armenia and Azerbaijan, US State Department, April 3, 2001. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ "Azerbaijani, South: A language of Iran" - Ethnologue report . Retrieved 07 June 2006.

- ↑ Azerbaijan, Human Development Report 2009. UN. Retrieved 29 May 2010

- ↑ Social Work: Assessment of social work practices, v.3 of Social Work, ISBN 8182051339. Gyan Publishing House, 2004; p.43

- ↑ "Report on corruption in Azerbaijan oil industry prepared for EBRD & IFC investigation arms", The Committee of Oil Industry Workers’ Rights Protection, October 2003 . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan: A New Muslim Ally for the U.S.?", FrontPageMagazine.com, May 22, 2006 . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ "The Crude Doctrine", Mother Jones, July/August, 2004 . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "Civil Society, Azerbaijan: Opposition parties prepare to vigorously contest parliamentary election", Eurasia.net, 3/28/05 . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ ""Library of Congress Iran": Azarbaijanis". Lcweb2.loc.gov. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ir0052). Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ Higgins, Patricia J. (1984) "Minority-State Relations in Contemporary Iran" Iranian Studies 17(1): pp. 37-71, p. 59

- ↑ Binder, Leonard (1962) Iran: Political Development in a Changing Society University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., pp. 160-161, OCLC 408909

- ↑ Ervand Abrahamian, Iran between Two Revolutions, Princeton University Press (1982), ISBN 0-691-10134-5 . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ David Menashri, "Shi'ite Leadership: In the Shadow of Conflicting Ideologies", Iranian Studies, 13:1–4 (1980) . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ "Archive Pages". Iranian.com. http://www.iranian.com/Satire/Cartoon/2006/June/soosks.html. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ "Ethnic Tensions Over Cartoon Set Off Riots in Northwest Iran", The New York Times . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ "Iran Azeris protest over cartoon", BBC News . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ "Cockroach Cartoonist Jailed In Iran", The Comics Reporter, May 24, 2006 . Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- ↑ "Iranian paper banned over cartoon" , BBC News, May 23, 2006 . Retrieved 15 June 2006.

- ↑ Burke, Andrew. Iran. Lonely Planet, Nov 1, 2004, P 42–43. ISBN 1-74059-425-8

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "Azerbaijan-Iran tensions increasing". BBC News. 2010-02-14. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/8515588.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 H. Javadi and K. Burill, "x. Azeri Literature in Iran", Encyclopedia Iranica, . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ "Contemporary Literature", Azerbaijan International, Spring 1996, (4.1) . Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ↑ Ronald G. Suny. Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. DIANE Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0788128132; p.105

- ↑ (Russian) Ethnic Composition of Azerbaijan by Arif Yunusov. Demoscope.ru. 2004. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ↑ [4] SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS SURVEY OF IRANIAN HOUSEHOLDS (2002)(Amârgiri az vizhegihâ-ye ejtemâ’i eqtesadi-ye khânevâr. Tehran, Markaz-e amâr-e irân, 1382),CNRS, Université Paris III, INaLCO, EPHE,Paris,page 14.

- ↑ Boyle, Kevin and Juliet Sheen. Freedom of Religion and Belief. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-415-15978-4; p. 273

- ↑ "Azerbaijan", US State Department, October 26, 2001 . Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Internal Factors of Islam's Radicalisation in the Caucasus. RIA Dagestan.(Turkish language)

- ↑ 5,000 Azeris adopted Christianity. Day.az. Published and retrieved 7 July 2007 (Turkish language)

- ↑ Azerbaijan: Culture and Art. Embassy of the Azerbaijan Republic in the People's Republic of China.

- ↑ "ISN Security Watch — Azerbaijan young increasingly drawn to Islam". Isn.ethz.ch. http://www.isn.ethz.ch/isn/Current-Affairs/Security-Watch/Detail/?ots591=4888CAA0-B3DB-1461-98B9-E20E7B9C13D4&lng=en&id=53700. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=27947

- ↑ "Avaz", Stanford University Persian Student Association . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ "Guba", Azerbaijan: The Land of the Arts . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ "Hossein Alizadeh Personal Reflections on Playing Tar", Azerbaijan International, Winter 1997 . Retrieved 11 June 2006. (Turkish language)

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 "Azerbaijan", Sports history of Azerbaijanis . Retrieved 24 June 2006.

- ↑ "The Ministry of Youth and Sports", Azerbaijan International, Winter 1996 . Retrieved 11 June 2006.

- ↑ "Civil Society, Democratization & Development in Azerbaijan", The Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University, 4.28.05 . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ "Iranian Azeris: A Giant Minority", Policy Watch/Policy Peace, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy . Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ "US Suffrage Movement Timeline, 1792 to present", Susan B. Anthony Center for Women's Leadership. Retrieved 19 August 2006.

- ↑ "Azerbaijan: Women", OnlineWomen . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ "Women's rights in Azerbaijan", OneWomen . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ Azeri Women in Transition: Women in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan by Farideh Heyat, ISBN 0-7007-1662-9 . Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- ↑ Gender Panorama: Elections to the Milli Majlis of the Republic of Azerbaijan appointed on November 6, 2005, Azerbaijan Gender Information Centre . Retrieved 3 September 2006. Web archive link

- ↑ Abortion Policies: a Global Review. v.1, p.41. United Nations Publications, 2001. ISBN 9211513510

- ↑ Iran: "Amnesty International calls for action to end discrimination against women", Amnesty International . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ "Iran: women's protest brutally attacked", Iranian, Jun 15, 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ↑ Iran: "Women's Gains at Risk in Iran's New Parliament", Women's Enews . Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- Important note: population statistics for Azerbaijanis (including those without a notation) in foreign countries were derived from various census counts, the UN, the CIA Factbook, Ethnologue, and the Joshua Project.

External links

- Embassy of Azerbaijan, Washington DC

- BBC News Europe Country Profile

- Encyclopedia of the Orient: Azerbaijan

- The BBC Azeri news site written in Azeri language

- Azeri.net

- Azerbaijan International Magazine

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||